PROTECTED SPECIES

- Mike Brainard, Coordinator

- (228) 523-4057

- mike.brainard@dmr.ms.gov

IMPORTANT REPORTING INFORMATION

Stranded Sea Turtles – Harrison and Hancock Counties – IMMS hotline – 888-767-3657 | Jackson County – NOAA – 228-369-4796

Stranded Dolphins – IMMS hotline – 888-767-3657 | NOAA hotline – 877-WHALE-HELP (942-5343)

Manatee Sightings – DISL Manatee Sighting Network – 866-493-5803

Stranded, injured, or dead Gulf Sturgeon – NOAA Fisheries – 844-STURG-911 (788-7491)

Gopher Tortoise Reports – email jennifer.frey@mmns.ms.gov or call 228-493-0865

MDMR is the state agency responsible for overseeing the conservation and management of the state’s marine environment and its resources, which include all species subject to the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. In 2018, via a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and the MS Department of Environmental Quality, the MDMR received funding to create a position for a Protected Species Coordinator. This position has allowed the MDMR to work more effectively with other state, federal and private partners to ensure a more cohesive response to any threats or issues that impact Mississippi’s marine protected species.

The MDMR has a memorandum of agreement with the Institute for Marine Mammal Studies (IMMS) for assistance with dolphins, sea turtles and manatees that are impacted by both natural and anthropogenic factors. These sick and injured animals need to be taken care of and evaluated to determine the cause of their stranding. Also, carcasses need to be studied for the same reasons.

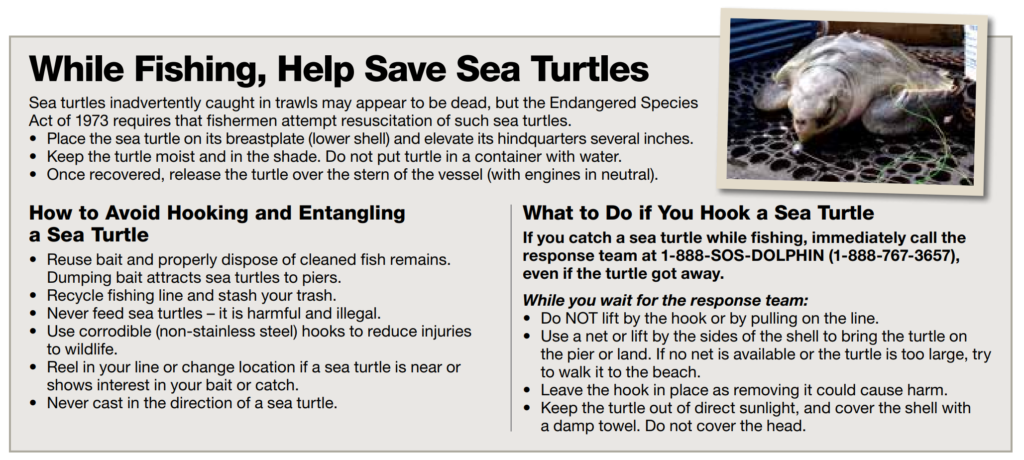

SEA TURTLES

The MDMR Office of Marine Fisheries works in cooperation with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in coordinating marine turtle protection issues in Mississippi coastal waters. The MDMR also participates in the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN), a division of NMFS, which, in addition to collecting mortality and stranding information on marine turtles, has the ability to provide veterinary services and holding facilities for rehabilitating stranded marine turtles through partners.

Above photos from the Rancho Nuevo, Mexico, joint U.S./Mexico effort to protect and increase the production of Kemp’s ridley sea turtles on their natural beaches.

The nesting season for the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, the most common sea turtle encountered along the Mississippi Gulf Coast, is from April through August of each year. They are the only sea turtle which routinely nests in the daytime. They also tend to nest in large nesting aggregations called “arribadas.” Their nesting range is from Galveston, Texas, to Tamaulipas, Mexico, with the majority of the population (about 95%) nesting in Rancho Nuevo, Mexico.

For the Kemp’s ridley, the average clutch size is 100 eggs. Nesting females will, on average, lay 2-3 clutches per season. When nests are located on the beaches of Rancho Nuevo, the eggs are relocated to a safe, enclosed area called a corral. Corrals keep nests safe by keeping predators and unauthorized humans away from the nest cavity. Turtle eggs are only relocated by trained and permitted sea turtle staff.

The incubation period for a nest ranges from 48 to 62 days, depending on air temperature. The temperature within the nest will affect the sex ratio of the nest. Incubation temperatures above 29.5 degrees Celsius tend to produce female offspring and the opposite will produce males. Lower spring incubation temperatures, for example, would tend to produce a large proportion of male babies. When a hatchling completes incubation, it uses a small egg tooth to break out of its leathery egg. Hatchlings are born with small yolk sacs that they must fully absorb before crawling out to sea. It often takes a baby sea turtle about 48-72 hours to make it to the ocean after it leaves the egg. When the majority of the hatchlings are ready to go, the nests begin where they get a burst of energy to help them crawl out of their nest and make it down to the water. This typically happens at nightfall.

MARINE MAMMALS

BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS

Bottlenose dolphins are not endangered or threatened; however, they are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. They are exposed to many stressors and threats including disease, biotoxin, pollution, habitat alteration, vessel collisions, human feeding and activities causing harassment, interactions with commercial and recreational fishing, energy exploration and oil spills and other types of human disturbance (such as underwater noise).

The Mississippi Sound, Lake Borgne, Bay Boudreau Stock area (“MS Sound Region”) is one of 38 separate groups in the Gulf of Mexico. Bottlenose dolphins follow their prey through the use of echolocation. They can make up to 1,000 clicking noises per second. These sounds travel underwater until they encounter objects, then bounce back to their dolphin senders, revealing the location, size and shape of their target. When dolphins are feeding, that target is often a bottom-dwelling fish, though they also eat shrimp and squid. These clever animals are also sometimes spotted following fishing boats in hopes of dining on leftovers.

Photos courtesy of IMMS

WEST INDIAN MANATEES (MANATEES)

Manatees are protected under federal law by the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which makes it illegal to harass, hunt, capture or kill any marine mammal. Manatees can be found in shallow, slow-moving rivers, estuaries, saltwater bays, canals and coastal areas. Particularly where seagrass beds or freshwater vegetation occur. Manatees are a migratory species. They are concentrated in Florida in the winter around warm water springs. In summer months, they can be found as far west as Texas and as far north as Massachusetts. Summer sightings in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana are common.

Manatees have no natural enemies and can live in excess of 60 years. As with all wild animal populations, a certain percentage of manatee mortality is attributed to natural causes of death. Unfortunately, a relatively high number of deaths are caused by accidents with vessels.

If you see a manatee while on or near the water, please call the Manatee Sighting Network at 866-866-493-5803 and ask the Protected Species Coordinator to have a sign to posted in the area warning vessel operators to slow down and beware of manatees in area.

Photos courtesy of USFWS

WHALES - RICE'S WHALE

In April 2019, NOAA listed the Gulf of Mexico Rice’s whale as “endangered” based upon the best available scientific and commercial information contained in the status review report. NOAA has determined that this species is presently in danger of extinction due to its small population size and restricted range, threats from energy exploration and development, oil spills and oil spill response, noise, vessel collisions and fishing gear entanglement. In 2021, scientists determined that the Rice’s whale was a unique species, genetically and morphologically distinct from Bryde’s whales. The Rice’s whale has been consistently located in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, along the continental shelf break between 100 and about 400 meters depth.

Photo courtesy of NOAA

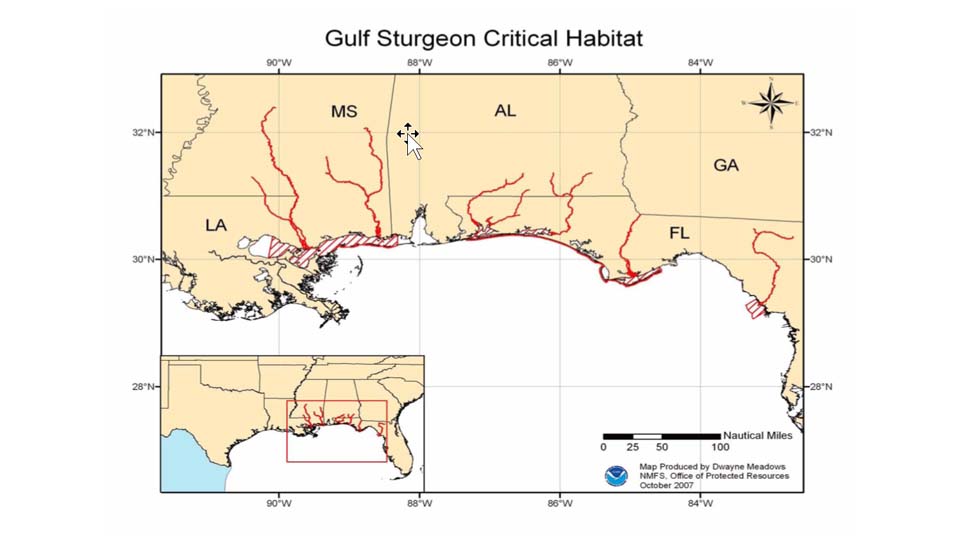

GULF STURGEON

The Gulf sturgeon is a sub-species of the Atlantic sturgeon that can be found from Lake Pontchartrain and the Pearl River system in Louisiana and Mississippi to the Suwannee River in Florida. Hatched in the freshwater of rivers, Gulf sturgeon head out to sea as juveniles, and return to the rivers of their birth to spawn (lay eggs) when they reach adulthood.

The Gulf sturgeon has five rows of bony plates known as scutes that run along its body and a snout with four barbels (slender, whisker-like, soft tissue projections) in front of its mouth. Similar to sharks, Gulf sturgeon have tails where one side, or lobe, is larger than the other. All these features give the fish its unique look.

In 1991, Gulf sturgeon were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act after their population was greatly reduced or eliminated throughout much of their range because of overfishing, dam construction and habitat degradation. NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service jointly manage and protect Gulf sturgeon.

Photo courtesy of USFWS